The first shuttle liftoff scheduled from Pad B, STS-51L was beset by delays. Launch was originally set for 3:43 p.m. EST, Jan. 22, 1986, slipped to Jan. 23, then Jan. 24, due to delays in mission 61-C. Launch was reset for Jan. 25 because of bad weather at the transoceanic abort landing (TAL) site in Dakar, Senegal. To utilize Casablanca (not equipped for night landings) as alternate TAL site, T-zero was moved to a morning liftoff time. The launch postponed another day when launch processing was unable to meet the new morning liftoff time. Prediction of unacceptable weather at KSC led to the launch being rescheduled for 9:37 a.m. EST, Jan. 27. The launch was delayed 24 hours again when the ground servicing equipment hatch closing fixture could not be removed from the orbiter hatch. The fixture was sawed off and an attaching bolt drilled out before closeout was completed. During the delay, cross winds exceeded return-to-launch-site limits at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility. The launch Jan. 28, 1986, was delayed two hours when a hardware interface module in the launch processing system, which monitors the fire detection system, failed during liquid hydrogen tanking procedures.

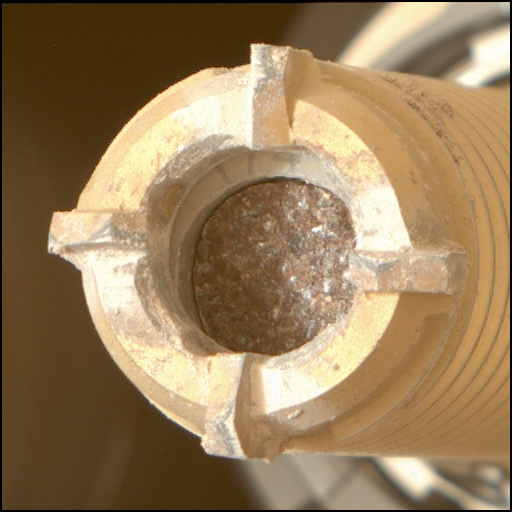

Just after liftoff at .678 seconds into the flight, photographic data shows a strong puff of gray smoke was spurting from the vicinity of the aft field joint on the right solid rocket booster. Computer graphic analysis of the film from the pad cameras indicated the initial smoke came from the 270 to 310-degree sector of the circumference of the aft field joint of the right solid rocket booster. This area of the solid booster faces the external tank. The vaporized material streaming from the joint indicated there was not a complete sealing action within the joint.

Eight more distinctive puffs of increasingly blacker smoke were recorded between .836 and 2.500 seconds. The smoke appeared to puff upwards from the joint. While each smoke puff was being left behind by the upward flight of the shuttle, the next fresh puff could be seen near the level of the joint. The multiple smoke puffs in this sequence occurred at about four times per second, approximating the frequency of the structural load dynamics and resultant joint flexing. As the shuttle increased its upward velocity, it flew past the emerging and expanding smoke puffs. The last smoke was seen above the field joint at 2.733 seconds.

The black color and dense composition of the smoke puffs suggest that the grease, joint insulation and rubber O-rings in the joint seal were being burned and eroded by the hot propellant gases.

At approximately 37 seconds, Challenger encountered the first of several high-altitude wind shear conditions, which lasted until about 64 seconds. The wind shear created forces on the vehicle with relatively large fluctuations. These were immediately sensed and countered by the guidance, navigation and control system. The steering system (thrust vector control) of the solid rocket booster responded to all commands and wind shear effects. The wind shear caused the steering system to be more active than on any previous flight.

Both the shuttle main engines and the solid rockets operated at reduced thrust approaching and passing through the area of maximum dynamic pressure of 720 pounds per square foot. The main engines had been throttled up to 104 percent thrust and the solid rocket boosters were increasing their thrust when the first flickering flame appeared on the right solid rocket booster in the area of the aft field joint. This first very small flame was detected on image enhanced film at 58.788 seconds into the flight. It appeared to originate at about 305 degrees around the booster circumference at or near the aft field joint.

One film frame later from the same camera, the flame was visible without image enhancement. It grew into a continuous, well-defined plume at 59.262 seconds. At about the same time (60 seconds), telemetry showed a pressure differential between the chamber pressures in the right and left boosters. The right booster chamber pressure was lower, confirming the growing leak in the area of the field joint.

As the flame plume increased in size, it was deflected rearward by the aerodynamic slipstream and circumferentially by the protruding structure of the upper ring attaching the booster to the external tank. These deflections directed the flame plume onto the surface of the external tank. This sequence of flame spreading is confirmed by analysis of the recovered wreckage. The growing flame also impinged on the strut attaching the solid rocket booster to the external tank.

The first visual indication that swirling flame from the right solid rocket booster breached the external tank was at 64.660 seconds when there was an abrupt change in the shape and color of the plume. This indicated that it was mixing with leaking hydrogen from the external tank. Telemetered changes in the hydrogen tank pressurization confirmed the leak. Within 45 milliseconds of the breach of the external tank, a bright sustained glow developed on the black-tiled underside of the Challenger between it and the external tank.

Beginning at about 72 seconds, a series of events occurred extremely rapidly that terminated the flight. Telemetered data indicated a wide variety of flight system actions that support the visual evidence of the photos as the shuttle struggled futilely against the forces that were destroying it.

At about 72.20 seconds the lower strut linking the solid rocket booster and the external tank was severed or pulled away from the weakened hydrogen tank permitting the right solid rocket booster to rotate around the upper attachment strut. This rotation is indicated by divergent yaw and pitch rates between the left and right solid rocket boosters.

At 73.124 seconds, a circumferential white vapor pattern was observed blooming from the side of the external tank bottom dome. This was the beginning of the structural failure of hydrogen tank that culminated in the entire aft dome dropping away. This released massive amounts of liquid hydrogen from the tank and created a sudden forward thrust of about 2.8 million pounds, pushing the hydrogen tank upward into the intertank structure. At about the same time, the rotating right solid rocket booster impacted the intertank structure and the lower part of the liquid oxygen tank. These structures failed at 73.137 seconds as evidenced by the white vapors appearing in the intertank region.

Within milliseconds there was massive, almost explosive, burning of the hydrogen streaming from the failed tank bottom and liquid oxygen breach in the area of the intertank.

At this point in its trajectory, while traveling at a Mach number of 1.92 at an altitude of 46,000 feet, Challenger was totally enveloped in the explosive burn. The Challenger’s reaction control system ruptured and a hypergolic burn of its propellants occurred as it exited the oxygen-hydrogen flames. The reddish brown colors of the hypergolic fuel burn are visible on the edge of the main fireball. The orbiter, under severe aerodynamic loads, broke into several large sections which emerged from the fireball. Separate sections that can be identified on film include the main engine/tail section with the engines still burning, one wing of the orbiter, and the forward fuselage trailing a mass of umbilical lines pulled loose from the payload bay.

The explosion 73 seconds after liftoff claimed crew and vehicle. The cause of explosion was determined to be an o-ring failure in the right solid rocket booster. Cold weather was determined to be a contributing factor.

Planned Orbital Activities

The planned orbital activities of the Challenger 51-L mission were as follows:

On Flight Day 1, after arriving into orbit, the crew was to have two periods of scheduled high activity. First they were to check the readiness of the TDRS-B satellite prior to planned deployment. After lunch they were to deploy the satellite and its Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) booster and to perform a series of separation maneuvers. The first sleep period was scheduled to be eight hours long starting about 18 hours after crew wakeup the morning of launch.

On Flight Day 2, the Comet Halley Active Monitoring Program (CHAMP) experiment was scheduled to begin. Also scheduled were the initial “teacher in space” (TISP) video taping and a firing of the orbital maneuvering engines (OMS) to place Challenger at the 152-mile orbital altitude from which the Spartan would be deployed.

On Flight Day 3, the crew was to begin pre-deployment preparations on the Spartan and then the satellite was to be deployed using the remote manipulator system (RMS) robot arm. Then the flight crew was to slowly separate from Spartan by 90 miles.

On Flight Day 4, the Challenger was to begin closing on Spartan while Gregory B. Jarvis continued fluid dynamics experiments started on day two and day 3. Live telecasts were also planned to be conducted by Christa McAuliffe.

On Flight Day 5, the crew was to rendezvous with Spartan and use the robot arm to capture the satellite and re-stow it in the payload bay.

On Flight Day 6, re-entry preparations were scheduled. This included flight control checks, test firing of maneuvering jets needed for re-entry, and cabin stowage. A crew news conferences was also scheduled following the lunch period.

On Flight Day 7, the day would have been spent preparing the Space Shuttle for deorbit and entry into the atmosphere. The Challenger was scheduled to land at the Kennedy Space Center 144 hours and 34 minutes after launch.